Dive into the captivating world of astrochemistry with Alexia Simon, a doctoral student at Harvard University.

Originally from France, Alexia conducts cutting-edge research on the chemistry of interstellar ice and its implications for star and planet formation. In this interview, she shares her inspiring journey, fascinating research, and vision for the future of space exploration.

My name is Alexia Simon and I’m from France. Currently, I’m in my sixth year of my Ph.D. at Harvard University, located in Cambridge, near Boston. I officially moved to Boston in 2019 to start my doctorate, but I had already begun doing internships in the United States since spring 2017.

A Field at the Intersection of Chemistry and Astronomy

Astrochemistry is “the study of chemical elements present in space and in astrophysical environments such as molecular clouds, where stars and planets form. It also encompasses the” study of the formation, interactions, and destruction of stars and planets.

Astrochemistry is a field of astronomy. My doctorate is within the astronomy department, where I’ve taken courses on various subjects, including galaxies, stars, exoplanets, cosmology, observational techniques with telescopes, as well as the study of planet formation, among others.

Let’s return to astrochemistry. This field is divided into three main subcategories: observation, theory, and laboratory experiments.

- Observation: This approach involves analyzing molecules present in protoplanetary disks, which are structures where planets are born. These observations can be made from Earth, using instruments like ALMA, or from space, thanks to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). They allow us to identify gas-phase molecules present in these environments. That said, thanks to JWST, for the first time, interstellar ice in protoplanetary disks.

- Theory: This part relies on simulations to understand the evolution of dust grains or small rocks or ice in protoplanetary disks. It focuses on solid-phase molecules and their chemical evolution in these environments.

- Laboratory experimentation: Experiments can focus on molecules in gas or solid phase. It’s important to note that in space, there is no liquid phase. Generally, gas-phase molecules end up in planetary atmospheres, while solid-phase ones are found in their internal structure.

My Missions

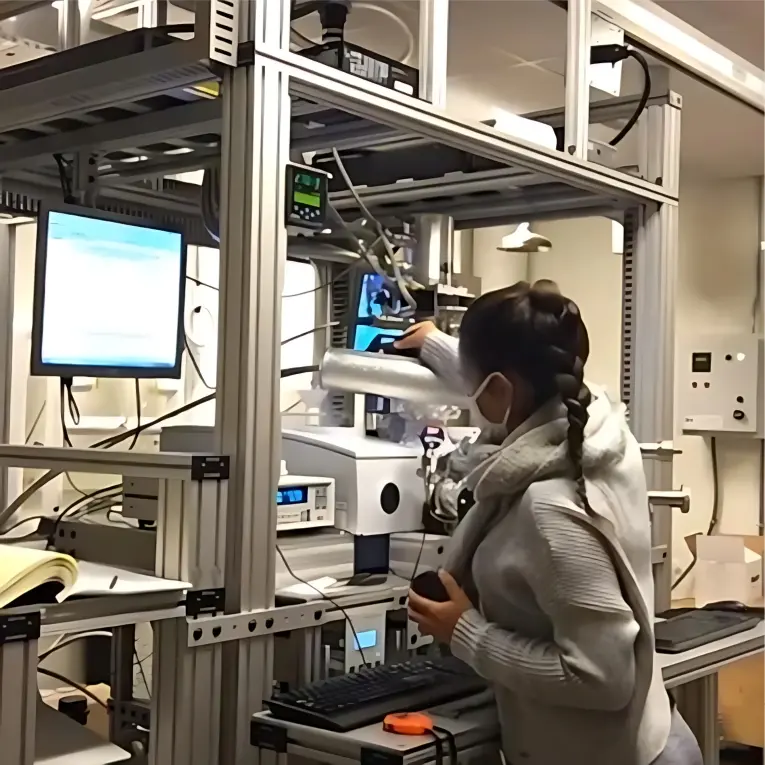

I specialize in laboratory experiments, in solid phase. My work involves reproducing chemical reactions that are likely to occur in space, particularly during the protoplanetary disk stage. These experiments allow us to discover new molecules potentially present in these environments or to understand the chemical mechanisms that help interpret astronomical observations. These three sub-fields – observation, theory, and laboratory – are interconnected and necessary to advance our understanding of the universe.

Understanding astrochemistry means analyzing molecules, chemical reactions in space, and their role at each stage of star and planet formation. This helps explain the composition of planetary bodies and their atmospheres. Moreover, it contributes to answering fundamental questions about the origin of life, particularly about the molecules necessary for its emergence.

A fascinating aspect of our field is that, in these protoplanetary disks, not all small rocks form planets. Some become asteroids or comets. In our Solar System, we have the opportunity to study these comets, often considered as preserved chemical archives from the beginnings of our system billions of years ago.

The exploration of the universe is one of the great human curiosities, just like the quest to understand our origins. Thanks to astrochemistry, we contribute to answering these essential questions.

My Journey

To begin with, I completed a scientific baccalaureate in high school, which I passed without honors. Then, I opted for a two-year DUT in chemistry at the IUT of Orsay (University of Paris-Sud). This choice better suited my learning method, as I’ve always enjoyed learning by doing, by carrying out concrete experiments – I’m a very “hands-on” person.

Professional relationships play an essential role in the academic world.

After my DUT (University Technology Diploma), I continued my studies with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry, still at Paris-Sud University in Orsay. During this period, my interest in astrochemistry strengthened through discussions with my professors. This led me to choose a master’s degree in chemistry at Pierre and Marie Curie University (Sorbonne University).

After my Master’s, I took a gap year to save money and prepare my application for American universities, particularly Harvard. Since applications to American universities were due in December, I had missed the deadline for the current year.

The application process for the United States: To apply, a complete application package was required, including:

- Three letters of recommendation,

- A personal statement,

- A CV,

- Responses to several questions about motivation, skills, academic performance, and extracurricular activities

- Proof of English proficiency (TOEFL or TOEIC),

- All diplomas obtained since high school, accompanied by official translations,

- Ideally, a scientific publication,

- The GRE (Graduate Record Examinations), which assesses general knowledge and the ability to succeed in graduate-level studies (master’s or doctoral).

These internships were crucial for my journey.

My Practical Experiences:

During my DUT, I did an internship in Valencia, Spain. During my two years of master’s, I also completed internships. In my first year, I worked at Georgia Tech (Atlanta, Georgia), and in my second year, I had the opportunity to do an internship in the laboratory where I am now pursuing my doctorate at Harvard.

These internships were crucial for my journey. During my Master’s 1, I had the chance to meet and also do a research project with a professor who advised me on the field of astrochemistry, after taking one of his courses on atmospheric chemistry. He directed me to a colleague at Georgia Tech, where I was able to deepen my knowledge. During this internship, I met other researchers and contacted my future thesis advisor at Harvard, sending her an email with a motivation letter and CV to ask for an internship opportunity.

Lessons Learned:

These experiences taught me that professional relationships play an essential role in academia. I had also heard that it was advantageous to have internship experience in the United States before applying for a doctorate in this country, which proved to be true.

The DUT brought me a lot, particularly great ease in the laboratory and confidence in my practical skills. The internships, in addition to teaching me to adapt to new countries and cultures, allowed me to develop qualities of adaptability and perseverance.

In parallel, during my higher education, summer holidays, or my gap year, I worked as a laboratory technician in the fields of biology, food science, and biopharmaceuticals. These experiences helped me better understand teamwork, decision-making, and the requirements of laboratory environments.

From my second year of DUT, I knew I wanted to specialize in astrochemistry. This field became a true passion and a clear goal that I pursued with determination throughout my academic and professional journey.

A Day with Me

A doctorate (PhD) typically lasts between 5 and 6 years. In my astronomy department, we have to meet several requirements:

- Courses: We must take about seven master’s level courses, usually two courses per semester. These courses include very demanding weekly assignments, often lengthy, as well as exams, and book readings, which require rigorous time management.

- Teaching: We must also take on the role of teaching assistant for two semesters, supervising undergraduate, master’s, or sometimes even doctoral level courses. Our tasks are to attend the course, take notes, create assignments, grade them, grade exams, and teach tutorials.

Community Engagement:

Another requirement is to participate in a public engagement activity (“outreach”). For my part, I co-organized ComSciCon, a conference dedicated to students, aimed at helping them better communicate complex concepts in an academic setting.

Generally, these academic and pedagogical obligations extend over the first three or four years of the doctorate, in addition to research projects. During the first year, we must also pass an official entrance exam for the department, where we answer a jury on about a hundred questions covering all aspects of astronomy.

Research: On the research side, we regularly present our progress to a thesis committee (established from the first year). Around the third or fourth year, a research examination validates our transition from the status of thesis student to doctoral candidate.

A typical day: Each day is different in my field, as we work in a very active department. Almost every day, scientific presentations are organized, whether given by department members (composed of more than 850 people, including scientists, engineers, and staff) or by visiting researchers from around the world.

When I’m in the laboratory, a typical day usually starts around 8 AM and ends between 4 PM and 10 PM, depending on the duration of experiments. Some days may last only 5 hours, while others can “extend up to” 14 hours.

When I’m not in the laboratory, I work from my office. These days are dedicated to:

- analyzing data from my experiments,

- writing scientific articles,

- preparing presentations,

- organizing activities for departmental clubs,

- participating in conferences or collaborations.

The work varies greatly depending on priorities and deadlines, which makes each day unique. This diversity is one of the aspects I appreciate most in my role as an astrochemistry researcher.

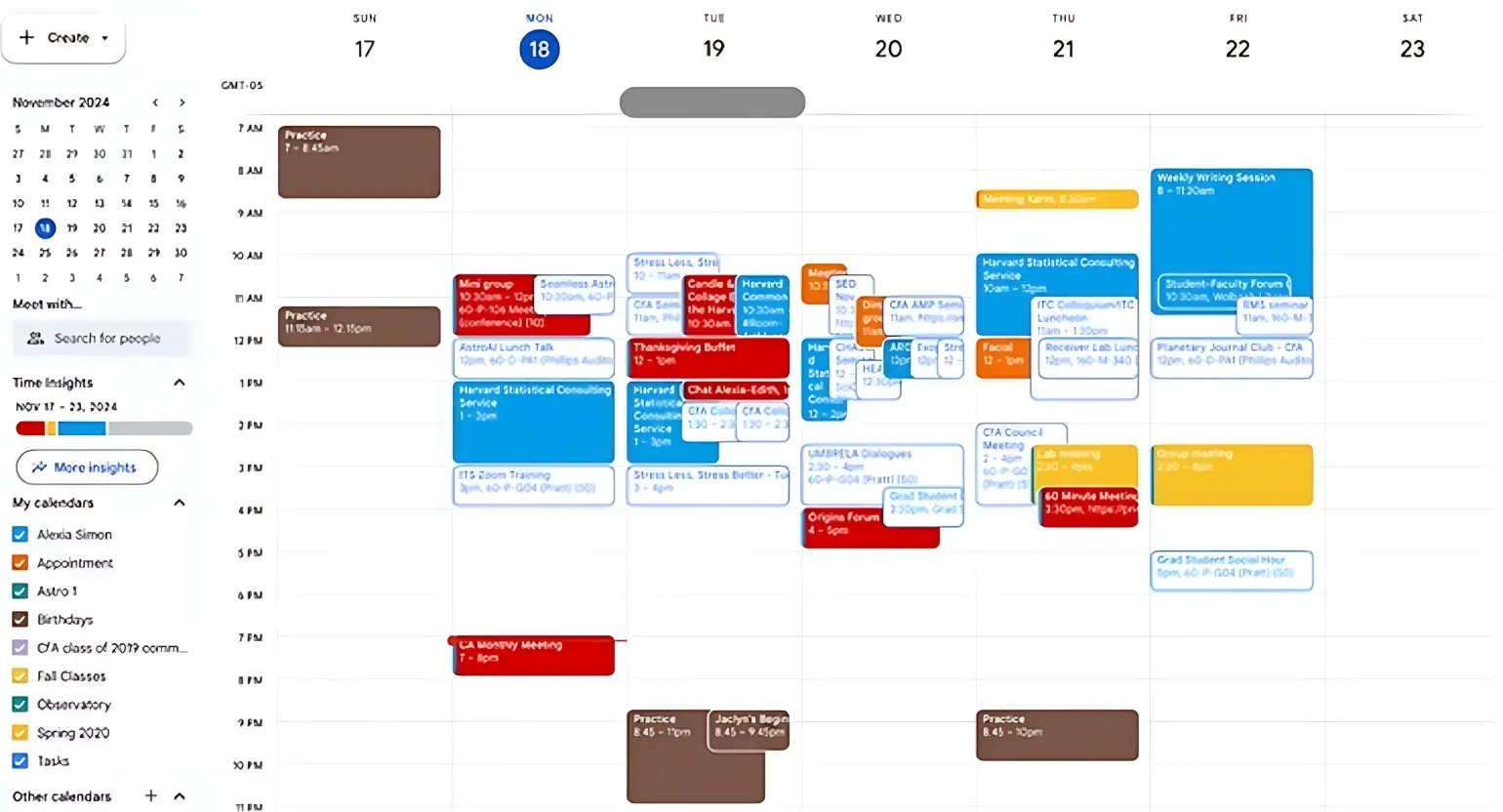

Here’s my Google calendar for a typical week this month:

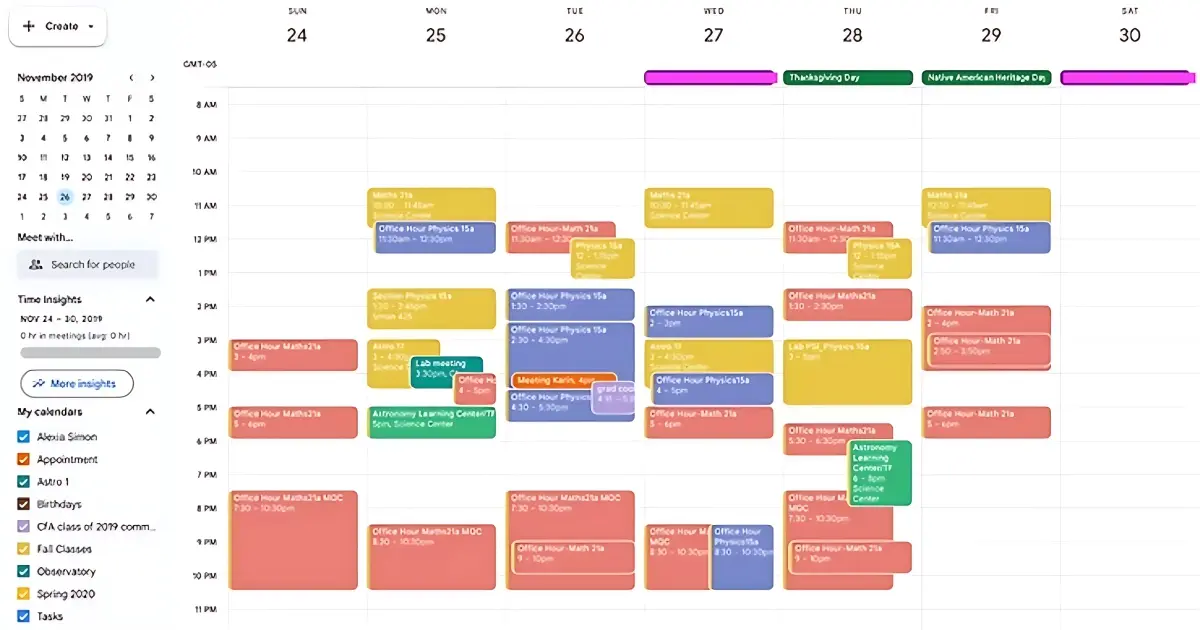

A typical week in November 2019 when I had classes:

Research on Interstellar Ice Chemistry

Understanding the mechanisms influencing molecule distribution in protoplanetary disks

I’m interested in molecules like H₂O, CO, CO₂, Argon, N₂, and CH₄, and I study how they are distributed between solid and gaseous phases in protoplanetary disks. These disks, which surround forming stars, have significant temperature gradients: regions close to the star can reach over 700°C, while the most distant areas can drop to -243°C. These temperature variations dictate whether a molecule is in solid or gaseous form. For example, just as water transitions from solid to gas when heated on Earth, a similar principle applies in space, although limited to solid and gaseous phases. By studying the chemical and physical mechanisms that govern these transitions, I seek to better understand which molecules are in which phase and where in the disks. This understanding is essential for determining where these molecules will eventually end up on forming planets: in their atmosphere or integrated into their internal structure.

Studying deuterium and its role in space chemical reactions

Another aspect of my research concerns deuterium, an isotope of hydrogen (the “most abundant element in the universe). I explore chemical reactions involving deuterium that can occur during the stages of star and planet formation. These reactions allow me to” study how deuterium-enriched molecules form and evolve. My goal is to compare the results of these experiments with observations of molecules present in comets, particularly their isotopic abundances. Comets, considered as “chemical archives” of the primitive Solar System, offer a unique opportunity to test models developed in the laboratory.

Specific Objectives:

Identify the processes that determine the phase of molecules in protoplanetary disks and understand their impact on the chemical composition of planets and their atmospheres.

Reveal the chemical mechanisms behind deuterium enrichment in certain molecules and link these results to astronomical observations, particularly in comets.

This research contributes to a better understanding of the fundamental processes of planet and star formation, while shedding light on the origins of molecules necessary for life.

My Experience in the USA

During my internship at the Georgia Tech Research Institute, under the supervision of Prof. Kenneth R. Brown, I worked on laboratory experiments aimed at measuring the different ro-vibrational states of the CaH⁺ molecular ion. This ion is a system of interest for fundamental studies, particularly in molecular physics and quantum chemistry, as it can serve as a model to better understand molecular interactions in specific environments.

Ro-vibrational spectroscopy is a technique used to study the energy transitions associated with the rotational and vibrational movements of molecules. These transitions are generally in the infrared range and provide precise information on molecular structure, bond strengths, and intramolecular interactions.

My work involved preparing the system, manipulating advanced spectroscopy equipment, and analyzing data to identify specific transitions between different ro-vibrational states. This project allowed me to immerse myself in a rigorous experimental approach and collaborate within a multidisciplinary team.

Impact of This Experience on My Current Research:

This experience has enriched my approach to current research on several levels:

- Discovery of the American Academic Environment: It was my first immersion in an academic environment in the United States. This allowed me to familiarize myself with a new scientific culture, improve my mastery of scientific English, and develop communication skills in an international environment.

- Autonomy in Project Management: This internship offered me the opportunity to work on an independent project, which taught me to be responsible, organize my time, and make scientific decisions autonomously. This autonomy helps me today in managing my thesis projects.

- Teamwork and Collaboration: Being integrated into a research team showed me the importance of interdisciplinary exchanges and collective work to advance on complex issues. This experience also made me aware of the importance of relying on the strengths of a group, a key skill in my current research in astrochemistry.

Launch of the James Webb Telescope in 2019

My project did not directly contribute to the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) in 2019, but it played a role in preparing for the interpretation of expected scientific results.

The JWST, thanks to its exceptional sensitivity in the infrared, allows for the first time to directly observe interstellar ices in cold and dense environments, such as molecular clouds where stars and planets form. These observations require solid databases and experimental models to identify and analyze the spectral signatures of molecules present in these ices.

In this context, my work consists of reproducing interstellar ices in the laboratory by simulating extreme space conditions, such as very low temperatures (-263°C or less) and low-pressure environments (10^-10 Torr knowing that on Earth we are at ~700 Torr). These experiments allow us to measure the infrared spectra of ices and identify the specific molecules they contain.

These experimental data serve as a reference for interpreting the spectra observed by the JWST. For example, they allow us to Identify present molecules, Understand chemical processes, Contribute to astrophysical models.

The objective of my project was therefore to provide a reliable experimental database and analytical tools to help astronomers interpret JWST observations.

What are the Major Challenges in your Field?

Astrochemistry is a relatively recent field, still in full exploration, which represents both a challenge and an opportunity. Many fundamental questions remain unanswered, and there is still a lot of research to be done to fill the gaps in our understanding.

The main challenges I encounter in my research are at several levels:

- Technologies and Resources: Laboratories, observations, and simulations require extremely sophisticated tools and equipment. In the laboratory, accurately reproducing the extreme conditions of interstellar space (such as very low temperatures or exposure to UV radiation) requires expensive and complex instruments. Moreover, astronomical observations depend on telescopes like JWST or ALMA, whose usage time is limited and highly competitive. Finally, theoretical simulations require significant computing resources and models that are still in development.

- A Field Under Construction: As astrochemistry is still young, there are few absolute certainties. This means we often have to work with hypotheses, using the best available information. This requires creativity to connect disparate elements and propose innovative hypotheses, but also rigor to ensure our conclusions are robust.

- Scientific Complexity: The phenomena we study, such as chemical reactions in interstellar ices or the extreme environments of protoplanetary disks, involve very complex processes that are often interconnected. For example, it can be difficult to isolate a specific chemical reaction or interpret a spectral signal when multiple processes are occurring simultaneously.

However, these challenges make our generation of scientists particularly essential. We have the responsibility and excitement of laying the first solid foundations of this field, formulating initial hypotheses, and developing the tools and approaches that will serve as the foundation for the astrochemistry of the future.

Professional and Personal Life

The university provides numerous facilities to promote well-being (a meditation center, massage, and yoga) as well as gymnasiums, swimming pools, tennis courts, and even a variety of sports clubs. It also organizes many events, which help to decompress and relax after long workdays.

I try to engage in a sports activity at least two to three times a week. I am part of the dance club and the figure skating club, two activities that allow me to escape and express my creativity. These moments of sport and leisure are precious for recharging my batteries and finding balance.

However, I sometimes go through periods where the balance between professional and personal life becomes difficult. Work-life balance is a challenge, and I can go weeks, even months, without finding time to devote to my hobbies. My life is often composed of ups and downs, but I always try to do my best to improve.

For this, I prioritize my mental health by consulting a specialist, and my physical health by taking care of my body, particularly by seeing a chiropractor. These steps help me maintain an overall balance and stay resilient in the face of the demands of my professional life.

Some Advice

I think my greatest personal achievement has been building a healthy and fulfilling research environment. Being surrounded by a group of incredible colleagues and guided by an inspiring and caring thesis director has allowed me to fully thrive in my work.

Every research project I work on fascinates me and nourishes my curiosity for the mysteries of the universe. I have the privilege of delving into fascinating details.

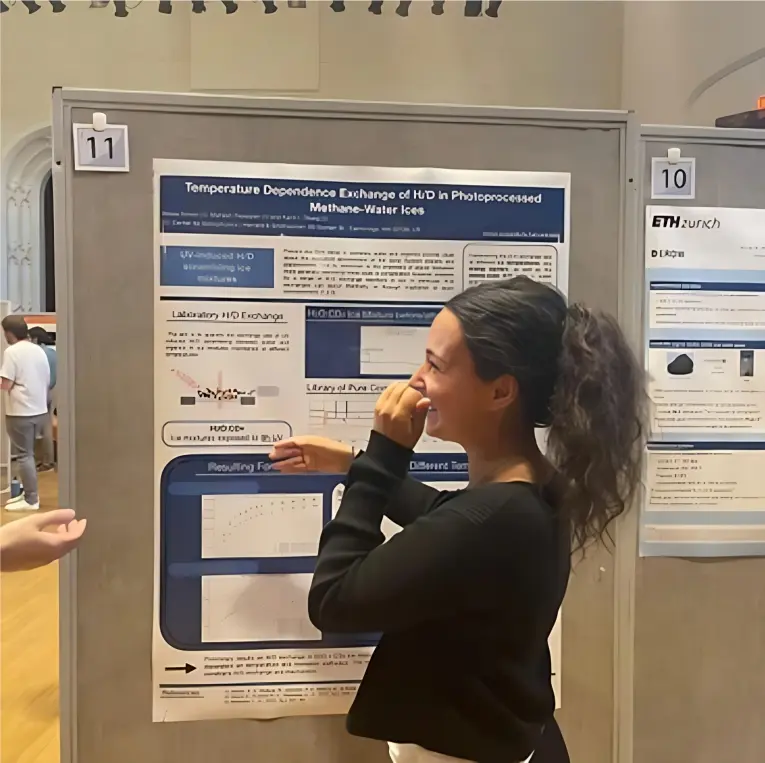

Another moment of great pride is the opportunity to share my research at conferences. These opportunities allow me to present my results, exchange ideas with researchers from around the world, and contribute to the collective progression of the field. Communicating my science, and seeing the interest it generates, represents an important achievement for me, both professionally and personally.

Outside of academia, the biggest lesson I’ve learned is the importance of persevering and communicating one’s goals and desires. I was never the ideal student: I didn’t graduate high school with honors, and I maintained average results for a good part of my studies. However, I learned to surround myself with good people, to dare to ask for help, and to seek advice from my professors or mentors.

This ability to create a support network and be proactive in my communication has been essential to me in the academic world, where collaboration and exchanges play a key role.

Another valuable lesson I’ve learned from my personal experiences is the importance of adaptability. I’ve worked in various environments, including as a laboratory technician, competition assistant, hostess, waitress, etc. These experiences taught me to quickly adapt to new teams, varied protocols, and different work rhythms. This flexibility is now a major asset in my research and also in my life, where priorities can change rapidly.

Finally, I’ve also learned that failure is not an end in itself, but a natural step in any development process. These experiences have taught me the importance of resilience and constructive reflection. Each difficulty encountered has pushed me to seek solutions, to improve, and to evolve, both professionally and personally.

I am grateful for the path I have traveled so far and for all the opportunities that have allowed me to learn, grow, and contribute, in my own way, to the understanding of the universe.

If I have a message to share, it would be to never underestimate the power of curiosity, perseverance, and never underestimate YOURSELF. No matter where you start from or the obstacles you encounter, dare to dream big and ask for help when you need it. Life is a collective adventure, and it’s by working together that we move forward. Some people will be there to help you, it can be hard but they exist.

Finally, I would like to thank all the people who have supported me throughout this journey. Each step has taught me something valuable, and I hope to inspire others to follow their passions and explore the unknown.

Contact Alexia here: alexia.simon@cfa.harvard.edu (response within 2 weeks)

Edited by Shyrin and Mazzarine